What is Glaucoma?

What causes Glaucoma?

How does Glaucoma affect the eye?

How do I know if my pet has Glaucoma?

How is Glaucoma treated?

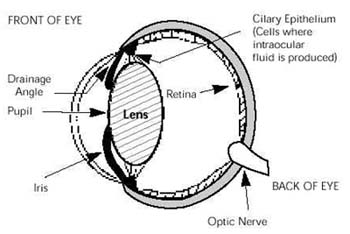

G laucoma is increased pressure within the eye (intraocular pressure = IOP ). Cells inside the eye produce a clear fluid (“aqueous humor”) that maintains the shape of the eye and nourishes the tissues inside the eye. (Note: aqueous humor is NOT the same fluid as tears. Tears bathe the outside surface of the eye. Aqueous humor circulates inside the eye. These two fluids do not interact). The aqueous humor drains out of the eye into the bloodstream through the drainage angle–a sieve or meshwork-like area through which aqueous percolates out of the eye. The balance of aqueous fluid production (“the faucet”) and drainage (“the drain in the sink”) is responsible for maintaining normal pressure inside the eye. In glaucoma, the drain becomes partially or completely clogged but the “faucet” steadily keeps producing aqueous, causing pressure to build inside the eye. If untreated, this increased pressure usually causes irreversible blindness, in addition to stretching and enlargement of the eye.

Many different conditions can cause glaucoma. Glaucoma is classified as either primary or secondary in animals.

Primary Glaucoma is an inherited condition. Primary glaucoma occurs in many breeds of dogs, including the American Cocker Spaniel, Basset Hound, Chow Chow, Shar Pei, Jack Russell Terrier, Shih Tzu, and Arctic Circle breeds (including the Siberian Husky and Elkhound). Primary glaucoma is rare in cats.

Primary Glaucoma usually begins in one eye, but in most patients it eventually affects both eyes, leading to complete blindness if not controlled.

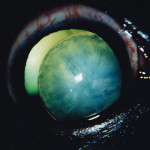

Chronic glaucoma in right eye of a dog, causing eye enlargement and secondary lens subluxation.

Secondary Glaucoma occurs when other eye diseases cause decreased drainage of fluid from the inside of the eye. Common causes of secondary glaucoma include: inflammation inside the eye (uveitis); advanced cataracts; cancer in the eye; lens subluxation or luxation (i.e. displacement of the lens from its normal position; a completely luxated lens is free of all attachments and can “float around” inside the eye, causing both damage and pain) and chronic retinal detachment. Glaucoma in cats is almost always secondary to chronic uveitis. Treatment for secondary glaucoma is too broad to be presented here; it is critical to treat the cause of the glaucoma whenever possible.

Patients are often more relaxed at our quiet and peaceful office, making it easier to obtain accurate IOPs.

Diagnosing whether your dog has primary or secondary glaucoma is important because the treatment needed and the prognosis for vision is different for each type of glaucoma. Veterinary ophthalmologists measure the intraocular pressure (IOP) and use slit lamp biomicroscopy, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and gonioscopy to determine the type and cause of glaucoma in your pet. Tonometry is measurement of IOP, and there are three basic types of instruments (tonometers) that can be used to measure IOP. The best tonometers are the TonoPen™ and the TonoVet™; these are costly computerized handheld devices. Another device is a Schiotz tonometer; this is an inexpensive stainless steel device, but is more difficult to use in animals. Gonioscopy helps determine how predisposed the remaining visual eye is to develop glaucoma when primary glaucoma is present in the other eye–i.e. what is the risk level of the remaining eye to develop glaucoma? Gonioscopy involves placing a special contact lens (“goniolens”) on the eye, which allows examination of the drainage angle. Gonioscopy is usually performed under sedation.

Unfortunately, the first eye to develop primary glaucoma in dogs is usually already irreversibly blind by the time glaucoma is diagnosed. For this reason, treatment for these patients is directed towards relieving discomfort (i.e. migraine headache) in the blind eye and trying to prevent or delay glaucoma from occurring in the other eye. Gonioscopy of the remaining visual eye helps determine how to best try to save this eye.

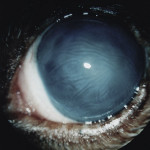

Acute Glaucoma in a Chow Chow. The eye is blind.

You don’t. The only way to know if your pet has glaucoma is to have the intraocular pressures (IOPs) measured (this is called “tonometry”) by a veterinarian, preferably a veterinary ophthalmologist. It can be difficult to accurately measure the IOP if the patient is in pain and/or agitated. Additionally, we have to contend with the “white coat effect”— this refers to the stress that a patient (dog, cat, or human) experiences when they visit their doctor’s office. This stress can cause temporarily increased blood pressure and/or increased eye pressure. Animals visiting their family veterinary clinic might be too anxious for staff to obtain an accurate IOP measurement. It is often necessary for patients with glaucoma to have their IOPs monitored at Animal Eye Care instead of at their family veterinary hospital because of stress-related issues; our office is quiet and peaceful. Sometimes this stress can be controlled at the family veterinary clinic by allowing the pet and owner to sit quietly in an exam room and dim the lights for 10-15 minutes before tonometry is performed. The key is a quiet, relaxed patient. Making the patient wait in a crowded, noisy reception area will interfere with obtaining an accurate IOP reading. If a general practitioner veterinarian diagnoses (or suspects) that glaucoma is present, the next step is to refer the patient to a veterinary ophthalmologist ASAP. The sooner that glaucoma is properly diagnosed and treated, the better.

Signs of glaucoma can include a red or bloodshot eye and/or cloudy cornea (the “clear windshield” part of the eye). Often the eye looks normal to the pet owner–or even to the general practitioner veterinarian–but it is not. Vision loss is also characteristic of glaucoma. However, loss of vision in one eye is usually not obvious because animals compensate very well by using their remaining visual eye. Eventually, the increased IOP will cause the eye to stretch and enlarge. Unfortunately, by the time the owner notices the enlarged eye, it is too late–eyes are permanently blind by the time they are obviously enlarged.

What if one eye is already lost to Primary Glaucoma? It is very likely that the remaining visual eye is at high risk for also developing glaucoma at a future time. Research has shown that the median time until a glaucoma attack occurs in the remaining visual eye is 8 months . However, prophylactic medical therapy and regular monitoring of the IOP for the remaining eye can delay the onset of glaucoma from a median of 8 months to a median of 31 months . The onset of a glaucoma attack might further be delayed by also providing the dog with a daily canine antioxidant vision supplement, Ocu-GLO™ (see www.OcuGLO.com ).

Since glaucoma occurs because fluid is not draining from the eye fast enough, the logical treatment is to open up the drain. Unfortunately, opening the drain and keeping it open is difficult in animals. Therefore, many glaucoma therapies are also aimed at decreasing fluid production by the eye.

A PERFECT SOLUTION FOR GLAUCOMA DOES NOT EXIST! AND… GLAUCOMA IS AN EXPENSIVE LIFETIME DISEASE TO TREAT, ESPECIALLY GENETIC GLAUCOMA IN DOGS.

(Dogs only): Endolaser Cyclophotocoagulation/lens removal/artificial lens placement/ +/- drainage device placement, FOLLOWED BY Lifetime Medical Therapy and CAM (Complementary and Alternative Medicine).

Cells in the eye that produce fluid are killed by a laser beam, after first removing the lens. Then an artificial lens is inserted, followed sometimes by inserting an artificial glaucoma drainage device.

Lifetime medical therapy and supplementation with canine antioxidant vision supplement (Ocu-GLO™); Control of stress; Use a harness attached to the leash instead of neck collar.

Lifetime regular IOP measurements/ophthalmic examinations

Lifetime Medical Therapy and CAM

Dogs and Cats: Topical (and sometimes oral) medication to control intraocular fluid production and increase fluid drainage. Lifetime regular IOP measurements/ophthalmic examinations

Dogs: Lifetime supplementation with canine antioxidant vision supplement (Ocu-GLO™); Control of stress; Use a harness attached to the leash instead of a neck collar.

Dogs and Cats: Lifetime regular IOP measurements/ophthalmic examinations.

Note for Cats: Treat cause of glaucoma; Control stress; Consider antioxidant supplementation.

Enucleation

Removal of the eye, and then the eyelids are sutured closed. This surgury is usually performed by your family veterinarian.

Enucleation and Orbital Prosthesis.Not recommended for cats.

Removal of the eye. A black prosthetic ball is then placed in the orbit and the eyelids sutured closed. It prevents “sunken-in” appearance of skin over eye socket. Performed at Animal Eye Care.

Evisceration and Intraocular Prosthesis

2 months post-operative appearance of eye with intraocular prosthesis.

The inside contents of the eye are removed and replaced with a prosthetic ball. This leaves your pet with a gray, non-painful eye that has no vision, but blinks and moves. Performed at Animal Eye Care.